While many of the examples in this book have focused on reading

files and looking for data in those files, there are many different

sources of information when one considers the Internet.

In this chapter we will pretend to be a web browser and retrieve web

pages using the HyperText Transport Protocol (HTTP). Then we will read

through the web page data and parse it.

12.1 HyperText Transport Protocol - HTTP

The network protocol that powers the web is actually quite simple and

there is built-in support in Python called sockets which makes it very

easy to make network connections and retrieve data over those

sockets in a Python program.

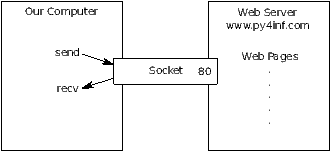

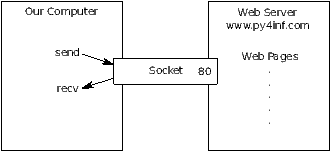

A socket is much like a file, except that it

provides a two-way connection between two

programs with a single socket.

You can both read from and write to the same socket. If you write something to

a socket it is sent to the application at the other end of the socket. If you

read from the socket, you are given the data which the other application has sent.

But if you try to read a socket when the program on the other end of the socket

has not sent any data - you just sit and wait. If the programs on both ends

of the socket simply wait for some data without sending anything, they will wait for

a very long time.

So an important part of programs that communicate over the Internet is to have some

sort of protocol. A protocol is a set of precise rules that determine who

is to go first, what they are to do, and then what are the responses to that message,

and who sends next and so on. In a sense the two applications at either end

of the socket are doing a dance and making sure not to step on each other's toes.

There are many documents which describe these network protocols. The HyperText Transport

Protocol is described in the following document:

http://www.w3.org/Protocols/rfc2616/rfc2616.txt

This is a long and complex 176 page document with a lot of detail. If you

find it interesting feel free to read it all. But if you take a look around page 36 of

RFC2616 you will find the syntax for the GET request. If you read in detail, you will

find that to request a document from a web server, we make a connection to

the www.py4inf.com server on port 80, and then send a line of the form:

GET http://www.py4inf.com/code/romeo.txt HTTP/1.0

Where the second parameter is the web page we are requesting and then

we also send a blank line. The web server will respond with some

header information about the document and a blank line

followed by the document content.

12.2 The World's Simplest Web Browser

Perhaps the easiest way to show how the HTTP protocol works is to write a very

simple Python program that makes a connection to a web server and following

the rules of the HTTP protocol, requests a document

and displays what the server sends back.

import socket

mysock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

mysock.connect(('www.py4inf.com', 80))

mysock.send('GET http://www.py4inf.com/code/romeo.txt HTTP/1.0\n\n')

while True:

data = mysock.recv(512)

if ( len(data) < 1 ) :

break

print data

mysock.close()

First the program makes a connection to port 80 on

the server www.py4inf.com.

Since our program is playing the role of the "web browser" the HTTP

protocol says we must send the GET command followed by a blank line.

Once we send that blank line, we write a loop that receives data

in 512 character chunks from the socket and prints the data out

until there is no more data to read (i.e. the recv() returns

an empty string).

The program produces the following output:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Sun, 14 Mar 2010 23:52:41 GMT

Server: Apache

Last-Modified: Tue, 29 Dec 2009 01:31:22 GMT

ETag: "143c1b33-a7-4b395bea"

Accept-Ranges: bytes

Content-Length: 167

Connection: close

Content-Type: text/plain

But soft what light through yonder window breaks

It is the east and Juliet is the sun

Arise fair sun and kill the envious moon

Who is already sick and pale with grief

The output starts with headers which the web server sends

to describe the document.

For example, the Content-Type header indicated that

the document is a plain text document (text/plain).

After the server sends us the headers, it adds a blank line

to indicate the end of the headers and then sends the actual

data of the file romeo.txt.

This example shows how to make a low-level network connection

with sockets. Sockets can be used to communicate with a web

server or with a mail server or many other kinds of servers.

All that is needed is to find the document which describes

the protocol and write the code to send and receive the data

according to the protocol.

However, since the protocol that we use most commonly is

the HTTP (i.e. the web) protocol, Python has a special

library specifically designed to support the HTTP protocol

for the retrieval of

documents and data over the web.

12.3 Retrieving an image over HTTP

In the above example, we retreived a plain text file

which had newlines in the file and we simply copied the

data to the screen as the program ran. We can use a similar

program to retrieve an image across using HTTP. Instead

of copying the data to the screen as the program runs,

we accumulate the data in a string, trim off the headers

and then save the image data to a file as follows:

import socket

import time

mysock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

mysock.connect(('www.py4inf.com', 80))

mysock.send('GET http://www.py4inf.com/cover.jpg HTTP/1.0\n\n')

count = 0

picture = "";

while True:

data = mysock.recv(5120)

if ( len(data) < 1 ) : break

# time.sleep(0.25)

count = count + len(data)

print len(data),count

picture = picture + data

mysock.close()

# Look for the end of the header (2 CRLF)

pos = picture.find("\r\n\r\n");

print 'Header length',pos

print picture[:pos]

# Skip past the header and save the picture data

picture = picture[pos+4:]

fhand = open("stuff.jpg","w")

fhand.write(picture);

fhand.close()

When the program runs it produces the following output:

$ python urljpeg.py

2920 2920

1460 4380

1460 5840

1460 7300

...

1460 62780

1460 64240

2920 67160

1460 68620

1681 70301

Header length 240

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Sat, 02 Nov 2013 02:15:07 GMT

Server: Apache

Last-Modified: Sat, 02 Nov 2013 02:01:26 GMT

ETag: "19c141-111a9-4ea280f8354b8"

Accept-Ranges: bytes

Content-Length: 70057

Connection: close

Content-Type: image/jpeg

You can see that that for this url, the

Content-Type header indicates that

body of the document is an image (image/jpeg).

Once the program completes, you can view the image data by opening

the file stuff.jpg in an image viewer.

As the program runs,

can see that we don't get 5120 characters each time we

call the recv() method.

We get as many characters that have been transfered across the network

to us by the web server at the moment we call recv().

In this example, we either get 1460 or

2920 characters each time we request up to 5120 characters of data.

Your results may be different depending on your network speed. Also

note that on the last call to recv() we get 1681 bytes which is the end

of the stream and in the next call to recv() we get a zero length

string that tells us that the server has called close() on its end

of the socket and there is no more data forthcoming.

We can slow down our successive calls recv() by uncommmenting the call

to time.sleep(). This way, we wait a quarter of a second after each call

so that the server can "get ahead" of us and send more data to us

before we call recv(). With the delay in place the program

executes as follows:

$ python urljpeg.py

1460 1460

5120 6580

5120 11700

...

5120 62900

5120 68020

2281 70301

Header length 240

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Sat, 02 Nov 2013 02:22:04 GMT

Server: Apache

Last-Modified: Sat, 02 Nov 2013 02:01:26 GMT

ETag: "19c141-111a9-4ea280f8354b8"

Accept-Ranges: bytes

Content-Length: 70057

Connection: close

Content-Type: image/jpeg

Now other than the first and last calls to recv(), we now get

5120 characters each time we ask for new data.

There is a buffer between the server making send() requests

and our application making recv() requests. When we run the

program with the delay in place, at some point the server might

fill up the buffer in the socket and be forced to pause until our

program starts to empty the buffer. The pausing of either the

sending application or the receiving application is called

"flow control".

12.4 Retrieving web pages with urllib

While we can manually send and receive data over HTTP

using the socket library, there is a much simpler way to

to perform this common task in Python by

using the urllib library.

Using urllib,

you can treat a web page much like a file. You simply

indicate which web page you would like to retrieve and

urllib handles all of the HTTP protocol and header

details.

The equivalent code to read the romeo.txt file

from the web using urllib is as follows:

import urllib

fhand = urllib.urlopen('http://www.py4inf.com/code/romeo.txt')

for line in fhand:

print line.strip()

Once the web page has been opened with

urllib.urlopen we can treat it like

a file and read through it using a

for loop.

When the program runs, we only see the output

of the contents of the file. The headers

are still sent, but the urllib code

consumes the headers and only returns the

data to us.

But soft what light through yonder window breaks

It is the east and Juliet is the sun

Arise fair sun and kill the envious moon

Who is already sick and pale with grief

As an example, we can write

a program to retrieve the data for

romeo.txt and compute the frequency

of each word in the file as follows:

import urllib

counts = dict()

fhand = urllib.urlopen('http://www.py4inf.com/code/romeo.txt')

for line in fhand:

words = line.split()

for word in words:

counts[word] = counts.get(word,0) + 1

print counts

Again, once we have opened the web page,

we can read it like a local file.

12.5 Parsing HTML and scraping the web

One of the common uses of the urllib capability in Python is

to scrape the web. Web scraping is when we write a program

that pretends to be a web browser and retrieves pages and then

examines the data in those pages looking for patterns.

As an example, a search engine such as Google will look at the source

of one web page and extract the links to other pages and retrieve

those pages, extracting links, and so on. Using this technique,

Google spiders its way through nearly all of the pages on

the web.

Google also uses the frequency of links from pages it finds

to a particular page as one measure of how "important"

a page is and how highly the page should appear in its search results.

12.6 Parsing HTML using Regular Expressions

One simple way to parse HTML is to use regular expressions to repeatedly

search and extract for substrings that match a particular pattern.

Here is a simple web page:

<h1>The First Page</h1>

<p>

If you like, you can switch to the

<a href="http://www.dr-chuck.com/page2.htm">

Second Page</a>.

</p>

We can construct a well-formed regular expression to match

and extract the link values from the above text as follows:

href="http://.+?"

Our regular expression looks for strings that start with

"href="http://" followed by one or more characters

".+?" followed by another double quote. The question mark

added to the ".+?" indicates that the match is to be done

in a "non-greedy" fashion instead of a "greedy" fashion.

A non-greedy match tries to find the smallest possible matching

string and a greedy match tries to find the largest possible

matching string.

We need to add parentheses to our regular expression to indicate

which part of our matched string we would like to extract and

produce the following program:

import urllib

import re

url = raw_input('Enter - ')

html = urllib.urlopen(url).read()

links = re.findall('href="(http://.*?)"', html)

for link in links:

print link

The findall regular expression method will give us a list of all

of the strings that match our regular expression, returning only

the link text between the double quotes.

When we run the program, we get the following output:

python urlregex.py

Enter - http://www.dr-chuck.com/page1.htm

http://www.dr-chuck.com/page2.htm

python urlregex.py

Enter - http://www.py4inf.com/book.htm

http://www.greenteapress.com/thinkpython/thinkpython.html

http://allendowney.com/

http://www.py4inf.com/code

http://www.lib.umich.edu/espresso-book-machine

http://www.py4inf.com/py4inf-slides.zip

Regular expressions work very nice when your HTML is well-formatted

and predictable. But since there is a lot of "broken" HTML pages

out there, you might find that a solution only using

regular expressions might either miss some valid links or end up

with bad data.

This can be solved by using a robust HTML parsing library.

12.7 Parsing HTML using BeautifulSoup

There are a number of Python libraries which can help you parse

HTML and extract data from the pages. Each of the libraries

has its strengths and weaknesses and you can pick one based on

your needs.

As an example, we will simply parse some HTML input

and extract links using the BeautifulSoup library.

You can download and install the BeautifulSoup code

from:

www.crummy.com

You can download and "install" BeautifulSoup or you

can simply place the BeautifulSoup.py file in the

same folder as your application.

Even though HTML looks like XML and some pages are carefully

constructed to be XML, most HTML is generally broken in ways

that cause an XML parser to reject the entire page of HTML as

improperly formed. BeautifulSoup tolerates highly flawed

HTML and still lets you easily extract the data you need.

We will use urllib to read the page and then use

BeautifulSoup to extract the href attributes from the

anchor (a) tags.

import urllib

from BeautifulSoup import *

url = raw_input('Enter - ')

html = urllib.urlopen(url).read()

soup = BeautifulSoup(html)

# Retrieve all of the anchor tags

tags = soup('a')

for tag in tags:

print tag.get('href', None)

The program prompts for a web address, then opens the web

page, reads the data and passes the data to the BeautifulSoup

parser, and then retrieves all of the anchor tags and prints

out the href attribute for each tag.

When the program runs it looks as follows:

python urllinks.py

Enter - http://www.dr-chuck.com/page1.htm

http://www.dr-chuck.com/page2.htm

python urllinks.py

Enter - http://www.py4inf.com/book.htm

http://www.greenteapress.com/thinkpython/thinkpython.html

http://allendowney.com/

http://www.si502.com/

http://www.lib.umich.edu/espresso-book-machine

http://www.py4inf.com/code

http://www.pythonlearn.com/

You can use BeautifulSoup to pull out various parts of each

tag as follows:

import urllib

from BeautifulSoup import *

url = raw_input('Enter - ')

html = urllib.urlopen(url).read()

soup = BeautifulSoup(html)

# Retrieve all of the anchor tags

tags = soup('a')

for tag in tags:

# Look at the parts of a tag

print 'TAG:',tag

print 'URL:',tag.get('href', None)

print 'Content:',tag.contents[0]

print 'Attrs:',tag.attrs

This produces the following output:

python urllink2.py

Enter - http://www.dr-chuck.com/page1.htm

TAG: <a href="http://www.dr-chuck.com/page2.htm">

Second Page</a>

URL: http://www.dr-chuck.com/page2.htm

Content: [u'\nSecond Page']

Attrs: [(u'href', u'http://www.dr-chuck.com/page2.htm')]

These examples only begin to show the power of BeautifulSoup

when it comes to parsing HTML. See the documentation

and samples at

www.crummy.com

for more detail.

12.8 Reading binary files using urllib

Sometimes you want to retrieve a non-text (or binary) file such as

an image or video file. The data in these files is generally not

useful to print out but you can easily make a copy of a URL to a local

file on your hard disk using urllib.

The pattern is to open the URL and use read to download the entire

contents of the document into a string variable (img) and then write that

information to a local file as follows:

img = urllib.urlopen('http://www.py4inf.com/cover.jpg').read()

fhand = open('cover.jpg', 'w')

fhand.write(img)

fhand.close()

This program reads all of the data in at once across the network and

stores it in the variable img in the main memory of your computer

and then opens the file cover.jpg and writes the data out to your

disk. This will work if the size of the file is less than the size

of the memory of your computer.

However if this is a large audio or video file, this program may crash

or at least run extremely slowly when your computer runs out of memory.

In order to avoid running out of memory, we retrieve the data in blocks

(or buffers) and then write each block to your disk before retrieving

the next block. This way the program can read any sized file without

using up all of the memory you have in your computer.

import urllib

img = urllib.urlopen('http://www.py4inf.com/cover.jpg')

fhand = open('cover.jpg', 'w')

size = 0

while True:

info = img.read(100000)

if len(info) < 1 : break

size = size + len(info)

fhand.write(info)

print size,'characters copied.'

fhand.close()

In this example, we read only 100,000 characters at a time and then

write those characters to the cover.jpg file

before retrieving the next 100,000 characters of data from the

web.

This program runs as follows:

python curl2.py

568248 characters copied.

If you have a Unix or Macintosh computer, you probably have a command

built into your operating system that performs this operation

as follows:

curl -O http://www.py4inf.com/cover.jpg

The command curl is short for "copy URL" and so these two

examples are cleverly named curl1.py and curl2.py on

www.py4inf.com/code as they implement similar functionality

to the curl command. There is also a curl3.py sample

program that does this task a little more effectively in case you

actually want to use this pattern in a program you are writing.

12.9 Glossary

- BeautifulSoup:

- A Python library for parsing HTML documents

and extracting data from HTML documents

that compensates for most of the imperfections in the HTML that browsers

generally ignore.

You can download the BeautifulSoup code

from

www.crummy.com.

- port:

- A number that generally indicates which application

you are contacting when you make a socket connection to a server.

As an example, web traffic usually uses port 80 while e-mail

traffic uses port 25.

- scrape:

- When a program pretends to be a web browser and

retrieves a web page and then looks at the web page content.

Often programs are following the links in one page to find the next

page so they can traverse a network of pages or a social network.

- socket:

- A network connection between two applications

where the applications can send and receive data in either direction.

- spider:

- The act of a web search engine retrieving a page and

then all the pages linked from a page and so on until they have

nearly all of the pages on the Internet which they

use to build their search index.

Exercise 1

Change the socket program socket1.py to prompt the user for

the URL so it can read any web page.

You can use split('/') to break the URL into its component parts

so you can extract the host name for the socket connect call.

Add error checking using try and except to handle the condition where the

user enters an improperly formatted or non-existent URL.

Exercise 2

Change your socket program so that it counts the number of characters it has received

and stops displaying any text after it has shown 3000 characters. The program

should retrieve the entire document and count the total number of characters

and display the count of the number of characters at the end of the document.

Exercise 3

Use urllib to replicate the previous exercise of (1) retrieving the document

from a URL, (2) displaying up to 3000 characters, and (3) counting the overall number

of characters in the document. Don't worry about the headers for this exercise, simply

show the first 3000 characters of the document contents.

Exercise 4

Change the urllinks.py program to extract and count

paragraph (p) tags from the retrieved HTML document and

display the count of the paragraphs as the

output of your program.

Do not display the paragraph text - only count them.

Test your program on several small web pages

as well as some larger web pages.

Exercise 5

(Advanced) Change the socket program so that it only shows data after the

headers and a blank line have been received. Remember that recv is

receiving characters (newlines and all) - not lines.