7.1 Persistence

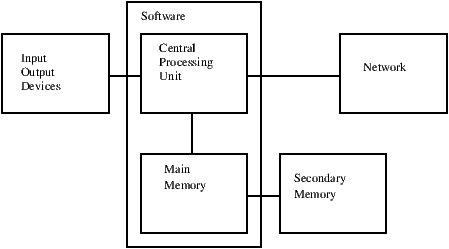

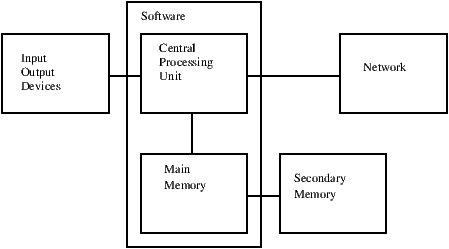

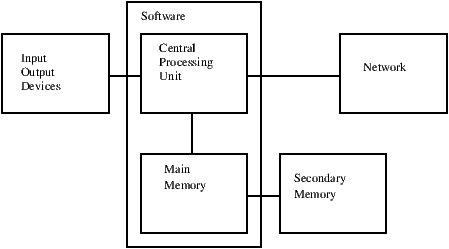

So far, we have learned how to write programs and communicate

our intentions to the Central Processing Unit using conditional

execution, functions, and iterations. We have learned how to

create and use data structures in the Main Memory. The CPU

and memory are where our software works and runs. It is where

all of the "thinking" happens.

But if you recall from our hardware architecture discussions,

once the power is turned off, anything stored in either

the CPU or main memory is erased. So up to now, our

programs have just been transient fun exercises to learn Python.

In this chapter, we start to work with Secondary Memory

(or files).

Secondary memory is not erased even when the power is turned off.

Or in the case of a USB flash drive, the

data can we write from our programs can be removed from the

system and transported to another system.

We will primarily focus on reading and writing text files such as

those we create in a text editor. Later we will see how to work

with database files which are binary files, specifically designed to be read

and written through database software.

7.2 Opening files

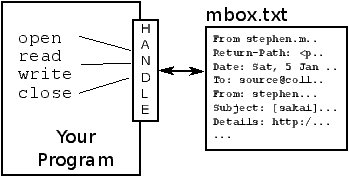

When we want to read or write a file (say on your hard drive), we first

must open the file. Opening the file communicates with your operating

system which knows where the data for each file is stored. When you open

a file, you are asking the operating system to find the file by name

and make sure the file exists. In this example, we open the file

mbox.txt which should be stored in the same folder that you

are in when you

start Python.

You can download this file from

www.py4inf.com/code/mbox.txt

>>> fhand = open('mbox.txt')

>>> print fhand

<open file 'mbox.txt', mode 'r' at 0x1005088b0>

If the open is successful, the operating system returns us a

file handle. The file handle is not the actual data contained

in the file, but instead it is a "handle" that we can use to

read the data. You are given a handle if the requested file

exists and you have the proper permissions to read the file.

If the file does not exist, open will fail with a traceback and you

will not get a handle to access the contents of the file:

>>> fhand = open('stuff.txt')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

IOError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'stuff.txt'

Later we will use try and except to deal more gracefully

with the situation where we attempt to open a file that does

not exist.

7.3 Text files and lines

A text file can be thought of as a sequence of lines, much like a Python

string can be thought of as a sequence of characters. For example, this

is a sample of a text file which records mail activity from various

individuals in an open source project development team:

From stephen.marquard@uct.ac.za Sat Jan 5 09:14:16 2008

Return-Path: <postmaster@collab.sakaiproject.org>

Date: Sat, 5 Jan 2008 09:12:18 -0500

To: source@collab.sakaiproject.org

From: stephen.marquard@uct.ac.za

Subject: [sakai] svn commit: r39772 - content/branches/

Details: http://source.sakaiproject.org/viewsvn/?view=rev&rev=39772

...

The entire file of mail interactions is available from

www.py4inf.com/code/mbox.txt

and a shortened version of the file is available from

www.py4inf.com/code/mbox-short.txt.

These files are in a standard format for a file containing

multiple mail messages. The lines which start with

"From " separate the messages and the lines which start

with "From:" are part of the messages.

For more information, see

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mbox.

To break the file into lines, there is a special character that

represents the "end of the line" called the newline character.

In Python, we represent the newline character as a backslash-n in

string constants. Even though this looks like two characters, it

is actually a single character. When we look at the variable by entering

"stuff" in the interpreter, it shows us the \n in the string,

but when we use print to show the string, we see the string broken

into two lines by the newline character.

>>> stuff = 'Hello\nWorld!'

>>> stuff

'Hello\nWorld!'

>>> print stuff

Hello

World!

>>> stuff = 'X\nY'

>>> print stuff

X

Y

>>> len(stuff)

3

You can also see that the length of the string 'X\nY' is three

characters because the newline character is a single character.

So when we look at the lines in a file, we need to imagine

that there is a special invisible character at the end of each line

that marks the end of the line called the newline.

So the newline character separates the characters

in the file into lines.

7.4 Reading files

While the file handle does not contain the data for the file,

it is quite easy to construct a for loop to read through

and count each of the lines in a file:

fhand = open('mbox.txt')

count = 0

for line in fhand:

count = count + 1

print 'Line Count:', count

python open.py

Line Count: 132045

We can use the file handle as the sequence in our for loop.

Our for loop simply counts the number of lines in the

file and prints them out. The rough translation of the for

loop into English is, "for each line in the file represented by the file

handle, add one to the count variable."

The reason that the open function does not read the entire file

is that the file might be quite large with many gigabytes of data.

The open statement takes the same amount of time regardless of the

size of the file. The for loop actually causes the data to be

read from the file.

When the file is read using a for loop in this manner, Python

takes care of splitting the data in the file into separate lines using

the newline character. Python reads each line through

the newline and includes

the newline as the last character in the line variable for each

iteration of the for loop.

Because the for loop reads the data one line at a time, it can efficiently

read and count the lines in very large files without running

out of main memory to store the data. The above program can

count the lines in any size file using very little memory since

each line is read, counted, and then discarded.

If you know the file is relatively small compared to the size of

your main memory, you can read the whole file into one string

using the read method on the file handle.

>>> fhand = open('mbox-short.txt')

>>> inp = fhand.read()

>>> print len(inp)

94626

>>> print inp[:20]

From stephen.marquar

In this example, the entire contents (all 94,626 characters)

of the file mbox-short.txt are read directly into the

variable inp. We use string slicing to print out the first

20 characters of the string data stored in inp.

When the file is read in this manner, all the characters including

all of the lines and newline characters are one big string

in the variable inp.

Remember that this form of the open function should only be used

if the file data will fit comfortably in the main memory

of your computer.

If the file is too large to fit in main memory, you should write

your program to read the file in chunks using a for or while

loop.

7.5 Searching through a file

When you are searching through data in a file, it

is a very common pattern to read through a file, ignoring most

of the lines and only processing lines which meet a particular criteria.

We can combine the pattern for reading a file with string methods

to build simple search mechanisms.

For example, if we wanted to read a file and only print out lines

which started with the prefix "From:", we could use the

string method startswith to select only those lines with

the desired prefix:

fhand = open('mbox-short.txt')

for line in fhand:

if line.startswith('From:') :

print line

When this program runs, we get the following output:

From: stephen.marquard@uct.ac.za

From: louis@media.berkeley.edu

From: zqian@umich.edu

From: rjlowe@iupui.edu

...

The output looks great since the only lines we are seeing are those

which start with "From:", but why are we seeing the extra blank

lines? This is due to that invisible newline character.

Each of the lines ends with a newline, so the print

statement prints the string in the variable line which includes

a newline and then print adds another newline, resulting

in the double spacing effect we see.

We could use line slicing to print all but the last character, but

a simpler approach is to use the rstrip method which strips

whitespace from the right side of a string as follows:

fhand = open('mbox-short.txt')

for line in fhand:

line = line.rstrip()

if line.startswith('From:') :

print line

When this program runs, we get the following output:

From: stephen.marquard@uct.ac.za

From: louis@media.berkeley.edu

From: zqian@umich.edu

From: rjlowe@iupui.edu

From: zqian@umich.edu

From: rjlowe@iupui.edu

From: cwen@iupui.edu

...

As your file processing programs get more complicated, you may want

to structure your search loops using continue. The basic idea

of the search loop is that you are looking for "interesting" lines

and effectively skipping "uninteresting" lines. And then when we

find an interesting line, we do something with that line.

We can structure the loop to follow the

pattern of skipping uninteresting lines as follows:

fhand = open('mbox-short.txt')

for line in fhand:

line = line.rstrip()

# Skip 'uninteresting lines'

if not line.startswith('From:') :

continue

# Process our 'interesting' line

print line

The output of the program is the same. In English, the

uninteresting lines are those which do not start

with "From:", which we skip using continue.

For the "interesting" lines (i.e. those that start with "From:")

we perform the processing on those lines.

We can use the find string method to simulate a text editor

search which finds lines where the search string is anywhere in the line.

Since find looks for an occurrence of a string within another

string and either returns the position of the string or -1 if the string

was not found, we can write the following loop to show lines which

contain the string "@uct.ac.za" (i.e. they come from the University

of Cape Town in South Africa):

fhand = open('mbox-short.txt')

for line in fhand:

line = line.rstrip()

if line.find('@uct.ac.za') == -1 :

continue

print line

Which produces the following output:

From stephen.marquard@uct.ac.za Sat Jan 5 09:14:16 2008

X-Authentication-Warning: set sender to stephen.marquard@uct.ac.za using -f

From: stephen.marquard@uct.ac.za

Author: stephen.marquard@uct.ac.za

From david.horwitz@uct.ac.za Fri Jan 4 07:02:32 2008

X-Authentication-Warning: set sender to david.horwitz@uct.ac.za using -f

From: david.horwitz@uct.ac.za

Author: david.horwitz@uct.ac.za

...

7.6 Letting the user choose the file name

We really do not want to have to edit our Python code

every time we want to process a different file. It would

be more usable to ask the user to enter the file name string

each time the program runs so they can use our

program on different files without changing the Python code.

This is quite simple to do by reading the file name from

the user using raw_input as follows:

fname = raw_input('Enter the file name: ')

fhand = open(fname)

count = 0

for line in fhand:

if line.startswith('Subject:') :

count = count + 1

print 'There were', count, 'subject lines in', fname

We read the file name from the user and place it in a variable

named fname and open that file. Now we can run the program

repeatedly on different files.

python search6.py

Enter the file name: mbox.txt

There were 1797 subject lines in mbox.txt

python search6.py

Enter the file name: mbox-short.txt

There were 27 subject lines in mbox-short.txt

Before peeking at the next section, take a look at the above program

and ask yourself, "What could go possibly wrong here?" or "What might our

friendly user do that would cause our nice little program to

ungracefully exit with a traceback, making us look not-so-cool

in the eyes of our users?".

7.7 Using try, except, and open

I told you not to peek. This is your last chance.

What if our user types something that is not a file name?

python search6.py

Enter the file name: missing.txt

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "search6.py", line 2, in <module>

fhand = open(fname)

IOError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'missing.txt'

python search6.py

Enter the file name: na na boo boo

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "search6.py", line 2, in <module>

fhand = open(fname)

IOError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'na na boo boo'

Do not laugh, users will eventually do every possible thing they can do

to break your programs --- either on purpose or with malicious intent.

As a matter of fact, an important part of any software development

team is a person or group called Quality Assurance (or QA for short)

whose very job it is to do the craziest things possible in an attempt

to break the software that the programmer has created.

The QA team is responsible for finding the flaws in programs before

we have delivered the program to the end-users who may be purchasing the

software or paying our salary to write the software. So the QA team

is the programmer's best friend.

So now that we see the flaw in the program, we can elegantly fix it using

the try/except structure. We need to assume that the open

call might fail and add recovery code when the open fails

as follows:

fname = raw_input('Enter the file name: ')

try:

fhand = open(fname)

except:

print 'File cannot be opened:', fname

exit()

count = 0

for line in fhand:

if line.startswith('Subject:') :

count = count + 1

print 'There were', count, 'subject lines in', fname

The exit function terminates the program. It is a function

that we call that never returns. Now when our user (or

QA team) types in silliness or bad file names,

we "catch" them and recover gracefully:

python search7.py

Enter the file name: mbox.txt

There were 1797 subject lines in mbox.txt

python search7.py

Enter the file name: na na boo boo

File cannot be opened: na na boo boo

Protecting the open call is a good example

of the proper use of try

and except in a Python program. We use the term

"Pythonic" when we are doing something the "Python

way". We might say that the above example is

the Pythonic way to open a file.

Once you become more skilled in Python, you can engage

in repartee' with other Python programmers to decide

which of two equivalent solutions to a problem is

"more Pythonic". The goal to be "more Pythonic"

captures the notion that programming is part engineering

and part art. We are not always interested

in just making something work, we also want

our solution to be elegant and to be appreciated as

elegant by our peers.

7.8 Writing files

To write a file, you have to open it with mode

'w' as a second parameter:

>>> fout = open('output.txt', 'w')

>>> print fout

<open file 'output.txt', mode 'w' at 0xb7eb2410>

If the file already exists, opening it in write mode clears out

the old data and starts fresh, so be careful!

If the file doesn't exist, a new one is created.

The write method of the file handle object

puts data into the file.

>>> line1 = 'This here's the wattle,\n'

>>> fout.write(line1)

Again, the file object keeps track of where it is, so if

you call write again, it adds the new data to the end.

We must make sure to manage the ends of lines as we write

to the file by explicitly inserting the newline character

when we want to end a line. The print statement

automatically appends a newline, but the write

method does not add the newline automatically.

>>> line2 = 'the emblem of our land.\n'

>>> fout.write(line2)

When you are done writing, you have to close the file

to make sure that the last bit of data is physically written

to the disk so it will not be lost if the power goes off.

>>> fout.close()

We could close the files which we open for read as well,

but we can be a little sloppy if we are only opening a few

files since Python makes sure that all open files are

closed when the program ends. When we are writing files,

we want to explicitly close the files so as to leave nothing

to chance.

7.9 Debugging

When you are reading and writing files, you might run into problems

with whitespace. These errors can be hard to debug because spaces,

tabs and newlines are normally invisible:

>>> s = '1 2\t 3\n 4'

>>> print s

1 2 3

4

The built-in function repr can help. It takes any object as an

argument and returns a string representation of the object. For

strings, it represents whitespace

characters with backslash sequences:

>>> print repr(s)

'1 2\t 3\n 4'

This can be helpful for debugging.

One other problem you might run into is that different systems

use different characters to indicate the end of a line. Some

systems use a newline, represented \n. Others use

a return character, represented \r. Some use both.

If you move files between different systems, these inconsistencies

might cause problems.

For most systems, there are applications to convert from one

format to another. You can find them (and read more about this

issue) at wikipedia.org/wiki/Newline. Or, of course, you

could write one yourself.

7.10 Glossary

- catch:

- To prevent an exception from terminating

a program using the try

and except statements.

- newline:

- A special character used in files and strings to indicate

the end of a line.

- Pythonic:

- A technique that works elegantly in Python.

"Using try and except is the Pythonic way to recover from

missing files.".

- Quality Assurance:

- A person or team focused on insuring the

overall quality of a software product. QA is often involved

in testing a product and identifying problems before the product

is released.

- text file:

- A sequence of characters stored in permanent

storage like a hard drive.

7.11 Exercises

Exercise 1

Write a program to read through a file and print the contents

of the file (line by line) all in upper case. Executing the program

will look as follows:

python shout.py

Enter a file name: mbox-short.txt

FROM STEPHEN.MARQUARD@UCT.AC.ZA SAT JAN 5 09:14:16 2008

RETURN-PATH: <POSTMASTER@COLLAB.SAKAIPROJECT.ORG>

RECEIVED: FROM MURDER (MAIL.UMICH.EDU [141.211.14.90])

BY FRANKENSTEIN.MAIL.UMICH.EDU (CYRUS V2.3.8) WITH LMTPA;

SAT, 05 JAN 2008 09:14:16 -0500

You can download the file from

www.py4inf.com/code/mbox-short.txt

Exercise 2

Write a program

to prompt for a file name, and then read through the file

and look for lines of the form:

X-DSPAM-Confidence: 0.8475

When you encounter a line that starts with

"X-DSPAM-Confidence:" pull apart the line to extract the

floating point number on the line. Count these

lines and the compute the total of the spam confidence

values from these lines.

When you reach the end of the file, print out the average

spam confidence.

Enter the file name: mbox.txt

Average spam confidence: 0.894128046745

Enter the file name: mbox-short.txt

Average spam confidence: 0.750718518519

Test your file on the mbox.txt and mbox-short.txt files.

Exercise 3

Sometimes when programmers get bored or want to have a bit of fun,

they add a harmless Easter Egg to their program

(en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Easter_egg_(media)). Modify the program

that prompts the user for the file name so that it prints a funny

message when the user types in the exact file name 'na na boo boo'.

The program should behave normally for all other files which exist

and don't exist. Here is a sample execution of the program:

python egg.py

Enter the file name: mbox.txt

There were 1797 subject lines in mbox.txt

python egg.py

Enter the file name: missing.tyxt

File cannot be opened: missing.tyxt

python egg.py

Enter the file name: na na boo boo

NA NA BOO BOO TO YOU - You have been punk'd!

We are not encouraging you to put Easter Eggs in your programs -

this is just an exercise.