Chapter 1 Why should you learn to write programs?

Writing programs (or programming) is a very creative

and rewarding activity. You can write programs for

many reasons ranging from making your living to solving

a difficult data analysis problem to having fun to helping

someone else solve a problem. This book assumes that

everyone needs to know how to program and that once

you know how to program, you will figure out what you want

to do with your newfound skills.

We are surrounded in our daily lives with computers ranging

from laptops to cell phones. We can think of these computers

as our "personal assistants" who can take care of many things

on our behalf. The hardware in our current-day computers

is essentially built to continuously ask us the question,

"What would you like me to do next?".

Programmers add an operating system and a set of applications

to the hardware and we end up with a Personal Digital

Assistant that is quite helpful and capable of helping

many different things.

Our computers are fast and have vast amounts of memory and

could be very helpful to us if we only knew the language to

speak to explain to the computer what we would like it to

"do next". If we knew this language we could tell the

computer to do tasks on our behalf that were repetitive.

Interestingly, the kinds of things computers can do best

are often the kinds of things that we humans find boring

and mind-numbing.

For example, look at the first three paragraphs of this

chapter and tell me the most commonly used word and how

many times the word is used. While you were able to read

and understand the words in a few seconds, counting them

is almost painful because it is not the kind of problem

that human minds are designed to solve. For a computer

the opposite is true, reading and understanding text

from a piece of paper is hard for a computer to do

but counting the words and telling you how many times

the most used word was used is very easy for the

computer:

python words.py

Enter file:words.txt

to 16

Our "personal information analysis assistant" quickly

told us that the word "to" was used sixteen times in the

first three paragraphs of this chapter.

This very fact that computers are good at things

that humans are not is why you need to become

skilled at talking "computer language". Once you learn

this new language, you can delegate mundane tasks

to your partner (the computer), leaving more time

for you to do the

things that you are uniquely suited for. You bring

creativity, intuition, and inventiveness to this

partnership.

1.1 Creativity and motivation

While this book is not intended for professional programmers, professional

programming can be a very rewarding job both financially and personally.

Building useful, elegant, and clever programs for others to use is a very

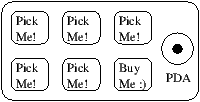

creative activity. Your computer or Personal Digital Assistant (PDA)

usually contains many different programs from many different groups of

programmers, each competing for your attention and interest. They try

their best to meet your needs and give you a great user experience in the

process. In some situations, when you choose a piece of software, the

programmers are directly compensated because of your choice.

If we think of programs as the creative output of groups of programmers,

perhaps the following figure is a more sensible version of our PDA:

For now, our primary motivation is not to make money or please end-users, but

instead for us to be more productive in handling the data and

information that we will encounter in our lives.

When you first start, you will be both the programmer and end-user of

your programs. As you gain skill as a programmer and

programming feels more creative to you, your thoughts may turn

toward developing programs for others.

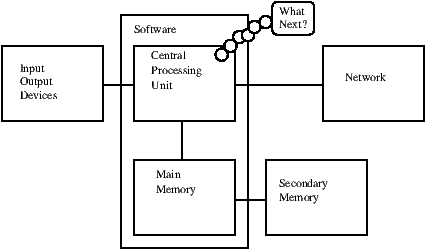

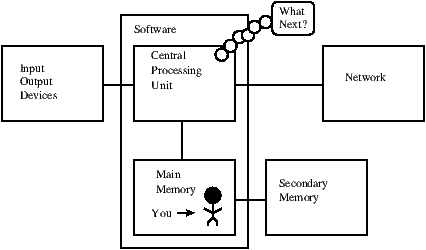

1.2 Computer hardware architecture

Before we start learning the language we

speak to give instructions to computers to

develop software, we need to learn a small amount about

how computers are built. If you were to take

apart your computer or cell phone and look deep

inside, you would find the following parts:

The high-level definitions of these parts are as follows:

- The Central Processing Unit (or CPU) is

that part of the computer that is built to be obsessed

with "what is next?". If your computer is rated

at 3.0 Gigahertz, it means that the CPU will ask "What next?"

three billion times per second. You are going to have to

learn how to talk fast to keep up with the CPU.

- The Main Memory is used to store information

that the CPU needs in a hurry. The main memory is nearly as

fast as the CPU. But the information stored in the main

memory vanishes when the computer is turned off.

- The Secondary Memory is also used to store

information, but it is much slower than the main memory.

The advantage of the secondary memory is that it can

store information even when there is no power to the

computer. Examples of secondary memory are disk drives

or flash memory (typically found in USB sticks and portable

music players).

- The Input and Output Devices are simply our

screen, keyboard, mouse, microphone, speaker, touchpad, etc.

They are all of the ways we interact with the computer.

- These days, most computers also have a

Network Connection to retrieve information over a network.

We can think of the network as a very slow place to store and

retrieve data that might not always be "up". So in a sense,

the network is a slower and at times unreliable form of

Secondary Memory

While most of the detail of how these components work is best left

to computer builders, it helps to have some terminology

so we can talk about these different parts as we write our programs.

As a programmer, your job is to use and orchestrate

each of these resources to solve the problem that you need solving

and analyze the data you need. As a programmer you will

mostly be "talking" to the CPU and telling it what to

do next. Sometimes you will tell the CPU to use the main memory,

secondary memory, network, or the input/output devices.

You need to be the person who answers the CPU's "What next?"

question. But it would be very uncomfortable to shrink you

down to 5mm tall and insert you into the computer just so you

could issue a command three billion times per second. So instead,

you must write down your instructions in advance.

We call these stored instructions a program and the act

of writing these instructions down and getting the instructions to

be correct programming.

1.3 Understanding programming

In the rest of this book, we will try to turn you into a person

who is skilled in the art of programming. In the end you will be a

programmer --- perhaps not a professional programmer but

at least you will have the skills to look at a data/information

analysis problem and develop a program to solve the problem.

In a sense, you need two skills to be a programmer:

- First you need to know the programming language (Python) -

you need to know the vocabulary and the grammar. You need to be able

spell the words in this new language properly and how to construct

well-formed "sentences" in this new languages.

- Second you need to "tell a story". In writing a story,

you combine words and sentences to convey an idea to the reader.

There is a skill and art in constructing the story and skill in

story writing is improved by doing some writing and getting some

feedback. In programming, our program is the "story" and the

problem you are trying to solve is the "idea".

Once you learn one programming language such as Python, you will

find it much easier to learn a second programming language such

as JavaScript or C++. The new programming language has very different

vocabulary and grammar but once you learn problem solving skills,

they will be the same across all programming languages.

You will learn the "vocabulary" and "sentences" of Python pretty quickly.

It will take longer for you to be able to write a coherent program

to solve a brand new problem. We teach programming much like we teach

writing. We start reading and explaining programs and then we write

simple programs and then write increasingly complex programs over time.

At some point you "get your muse" and see the patterns on your own

and can see more naturally how to take a problem and

write a program that solves that problem. And once you get

to that point, programming becomes a very pleasant and creative process.

We start with the vocabulary and structure of Python programs. Be patient

as the simple examples remind you of when you started reading for the first

time.

1.4 Words and sentences

Unlike human languages, the Python vocabulary is actually pretty small.

We call this "vocabulary" the "reserved words". These are words that

have very special meaning to Python. When Python sees these words in

a Python program, they have one and only one meaning to Python. Later

as you write programs you will make your own words that have meaning to

you called variables. You will have great latitude in choosing

your names for your variables, but you cannot use any of Python's

reserved words as a name for a variable.

In a sense, when we train a dog, we would use special words like,

"sit", "stay", and "fetch". Also when you talk to a dog and

don't use any of the reserved words, they just look at you with a

quizzical look on their faces until you say a reserved word.

For example, if you say,

"I wish more people would walk to improve their overall health.",

what most dogs likely hear is,

"blah blah blah walk blah blah blah blah."

That is because "walk" is a reserved word in dog language. Many

might suggest that the language between humans and cats has no

reserved words1.

The reserved words in the language where humans talk to

Python incudes the following:

and del for is raise

assert elif from lambda return

break else global not try

class except if or while

continue exec import pass yield

def ï¬ nally in print

That is it, and unlike a dog, Python is already completely trained.

When you say "try", Python will try every time you say it without

fail.

We will learn these reserved words and how they are used in good time,

but for now we will focus on the Python equivalent of "speak" (in

human to dog language). The nice thing about telling Python to speak

is that we can even tell it what to say by giving it a message in quotes:

print 'Hello world!'

And we have even written our first syntactically correct Python sentence.

Our sentence starts with the reserved word print followed

by a string of text of our choosing enclosed in single quotes.

1.5 Conversing with Python

Now that we have a word and a simple sentence that we know in Python,

we need to know how to start a conversation with Python to test

our new language skills.

Before you can converse with Python, you must first install the Python

software on your computer and learn how to start Python on your

computer. That is too much detail for this chapter so I suggest

that you consult www.pythonlearn.com where I have detailed

instructions and screencasts of setting up and starting Python

on Macintosh and Windows systems. At some point, you will be in

a terminal or command window and you will type python and

the Python interpreter will start executing in interactive mode:

and appear somewhat as follows:

Python 2.6.1 (r261:67515, Jun 24 2010, 21:47:49)

[GCC 4.2.1 (Apple Inc. build 5646)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

The >>> prompt is the Python interpreter's way of asking you, "What

do you want me to do next?". Python is ready to have a conversation with

you. All you have to know is how to speak the Python language and you

can have a conversation.

Lets say for example that you did not know even the simplest Python language

words or sentences. You might want to use the standard line that astronauts

use when they land on a far away planet and try to speak with the inhabitants

of the planet:

>>> I come in peace, please take me to your leader

File "<stdin>", line 1

I come in peace, please take me to your leader

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>>

This is not going so well. Unless you think of something quickly,

the inhabitants of the planet are likely to stab you with their spears,

put you on a spit, roast you over a fire, and eat you for dinner.

Luckily you brought a copy of this book on your travels and you thumb to

this very page and try again:

>>> print 'Hello world!'

Hello world!

This is looking much better so you try to communicate some

more:

>>> print 'You must be the legendary god that comes from the sky'

You must be the legendary god that comes from the sky

>>> print 'We have been waiting for you for a long time'

We have been waiting for you for a long time

>>> print 'Our legend says you will be very tasty with mustard'

Our legend says you will be very tasty with mustard

>>> print 'We will have a feast tonight unless you say

File "<stdin>", line 1

print 'We will have a feast tonight unless you say

^

SyntaxError: EOL while scanning string literal

>>>

The conversation was going so well for a while and then you

made the tiniest mistake using the Python language and Python

brought the spears back out.

At this point, you should also realize that while Python

is amazingly complex and powerful and very picky about

the syntax you use to communicate with it, Python is not intelligent. You are having a conversation with

yourself but using proper syntax.

In a sense when you use a program written by someone else

the conversation is between you and those other

programmers with Python acting as an intermediary. Python

is a way for the creators of programs to express how the

conversation is supposed to proceed. And

in just a few more chapters, you will be one of those

programmers using Python to talk to the users of your program.

Before we leave our first conversation with the Python

interpreter, you should probably know the proper way

to say "good-bye" when interacting with the inhabitants

of Planet Python:

>>> good-bye

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'good' is not defined

>>> if you don't mind, I need to leave

File "<stdin>", line 1

if you don't mind, I need to leave

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> quit()

You will notice that the error is different for the first two

incorrect attempts. The second error is different because

if is a reserved word and Python saw the reserved word

and thought we were trying to say something but got the syntax

of the sentence wrong.

The proper way to say "good-bye" to Python is to enter

quit() at the interactive chevron >>> prompt.

It would have probably taken you quite a while to guess that

one so having a book handy probably will turn out

to be helpful.

1.6 Terminology: interpreter and compiler

Python is a high-level language intended to be relatively

straightforward for humans to read and write and for computers

to read and process. Other high-level languages include: Java, C++,

PHP, Ruby, Basic, Perl, JavaScript, and many more. The actual hardware

inside the Central Processing Unit (CPU) does not understand any

of these high level languages.

The CPU understands a language we call machine-language. Machine

language is very simple and frankly very tiresome to write because it

is represented all in zeros and ones:

01010001110100100101010000001111

11100110000011101010010101101101

...

Machine language seems quite simple on the surface given that there

are only zeros and ones, but its syntax is even more complex

and far more intricate than Python. So very few programmers ever write

machine language. Instead we build various translators to allow

programmers to write in high level languages like Python or JavaScript

and these translators convert the programs to machine language for actual

execution by the CPU.

Since machine language is tied to the computer hardware, machine language

is not portable across different types of hardware. Programs written in

high-level languages can be moved between different computers by using a

different interpreter on the new machine or re-compiling the code to create

a machine language version of the program for the new machine.

These programming language translators fall into two general categories:

(1) interpreters and (2) compilers.

An interpreter reads the source code of the program as written by the

programmer, parses the source code, and interprets the instructions on-the-fly.

Python is an interpreter and when we are running Python interactively,

we can type a line of Python (a sentence) and Python processes it immediately

and is ready for us to type another line of Python.

Some of the lines of Python tell Python that you want it to remember some

value for later. We need to pick a name for that value to be remembered and

we can use that symbolic name to retrieve the value later. We use the

term variable to refer to the labels we use to refer to this stored data.

>>> x = 6

>>> print x

6

>>> y = x * 7

>>> print y

42

>>>

In this example, we ask Python to remember the value six and use the label x

so we can retrieve the value later. We verify that Python has actually remembered

the value using print. Then we ask Python to retrieve x and multiply

it by seven and put the newly-computed value in y. Then we ask Python to print out

the value currently in y.

Even though we are typing these commands into Python one line at a time, Python

is treating them as an ordered sequence of statements with later statements able

to retrieve data created in earlier statements. We are writing our first

simple paragraph with four sentences in a logical and meaningful order.

It is the nature of an interpreter to be able to have an interactive conversation

as shown above. A compiler needs to be handed the entire program in a file, and then

it runs a process to translate the high level source code into machine language

and then the compiler puts the resulting machine language into a file for later

execution.

If you have a Windows system, often these executable machine language programs have a

suffix of ".exe" or ".dll" which stand for "executable" and "dynamically loadable

library" respectively. In Linux and Macintosh there is no suffix that uniquely marks

a file as executable.

If you were to open an executable file in a text editor, it would look

completely crazy and be unreadable:

^?ELF^A^A^A^@^@^@^@^@^@^@^@^@^B^@^C^@^A^@^@^@\xa0\x82

^D^H4^@^@^@\x90^]^@^@^@^@^@^@4^@ ^@^G^@(^@$^@!^@^F^@

^@^@4^@^@^@4\x80^D^H4\x80^D^H\xe0^@^@^@\xe0^@^@^@^E

^@^@^@^D^@^@^@^C^@^@^@^T^A^@^@^T\x81^D^H^T\x81^D^H^S

^@^@^@^S^@^@^@^D^@^@^@^A^@^@^@^A\^D^HQVhT\x83^D^H\xe8

....

It is not easy to read or write machine language so it is nice that we have

interpreters and compilers that allow us to write in a high-level

language like Python or C.

Now at this point in our discussion of compilers and interpreters, you should

be wondering a bit about the Python interpreter itself. What language is

it written in? Is it written in a compiled language? When we type

"python", what exactly is happening?

The Python interpreter is written in a high level language called "C".

You can look at the actual source code for the Python interpreter by

going to www.python.org and working your way to their source code.

So Python is a program itself and it is compiled into machine code and

when you installed Python on your computer (or the vendor installed it),

you copied a machine-code copy of the translated Python program onto your

system. In Windows the executable machine code for Python itself is likely

in a file with a name like:

C:\Python27\python.exe

That is more than you really need to know to be a Python programmer, but

sometimes it pays to answer those little nagging questions right at

the beginning.

1.7 Writing a program

Typing commands into the Python interpreter is a great way to experiment

with Python's features, but it is not recommended for solving more complex problems.

When we want to write a program,

we use a text editor to write the Python instructions into a file,

which is called a script. By

convention, Python scripts have names that end with .py.

To execute the script, you have to tell the Python interpreter

the name of the file. In a Unix or Windows command window,

you would type python hello.py as follows:

csev$ cat hello.py

print 'Hello world!'

csev$ python hello.py

Hello world!

csev$

The "csev$" is the operating system prompt, and the "cat hello.py" is

showing us that the file "hello.py" has a one line Python program to print

a string.

We call the Python interpreter and tell it to read its source code from

the file "hello.py" instead of prompting us for lines of Python code

interactively.

You will notice that there was no need to have quit() at the end of

the Python program in the file. When Python is reading your source code

form a file, it knows to stop when it reaches the end of the file.

1.8 What is a program?

The definition of a program at its most basic is a sequence

of Python statements that have been crafted to do something.

Even our simple hello.py script is a program. It is a one-line

program and is not particularly useful, but in the strictest definition,

it is a Python program.

It might be easiest to understand what a program is by thinking about a problem

that a program might be built to solve, and then looking at a program

that would solve that problem.

Lets say you are doing Social Computing research on Facebook posts and

you are interested in the most frequently used word in a series of posts.

You could print out the stream of facebook posts and pore over the text

looking for the most common word, but that would take a long time and be very

mistake prone. You would be smart to write a Python program to handle the

task quickly and accurately so you can spend the weekend doing something

fun.

For example look at the following text about a clown and a car. Look at the

text and figure out the most common word and how many times it occurs.

the clown ran after the car and the car ran into the tent

and the tent fell down on the clown and the car

Then imagine that you are doing this task looking at millions of lines of

text. Frankly it would be quicker for you to learn Python and write a

Python program to count the words than it would be to manually

scan the words.

The even better news is that I already came up with a simple program to

find the most common word in a text file. I wrote it,

tested it, and now I am giving it to you to use so you can save some time.

name = raw_input('Enter file:')

handle = open(name, 'r')

text = handle.read()

words = text.split()

counts = dict()

for word in words:

counts[word] = counts.get(word,0) + 1

bigcount = None

bigword = None

for word,count in counts.items():

if bigcount is None or count > bigcount:

bigword = word

bigcount = count

print bigword, bigcount

You don't even need to know Python to use this program. You will need to get through

Chapter 10 of this book to fully understand the awesome Python techniques that were

used to make the program. You are the end user, you simply use the program and marvel

at its cleverness and how it saved you so much manual effort.

You simply type the code

into a file called words.py and run it or you download the source

code from http://www.pythonlearn.com/code/ and run it.

This is a good example of how Python and the Python language are acting as an intermediary

between you (the end-user) and me (the programmer). Python is a way for us to exchange useful

instruction sequences (i.e. programs) in a common language that can be used by anyone who

installs Python on their computer. So neither of us are talking to Python,

instead we are communicating with each other through Python.

1.9 The building blocks of programs

In the next few chapters, we will learn more about the vocabulary, sentence structure,

paragraph structure, and story structure of Python. We will learn about the powerful

capabilities of Python and how to compose those capabilities together to create useful

programs.

There are some low-level conceptual patterns that we use to construct programs. These

constructs are not just for Python programs, they are part of every programming language

from machine language up to the high-level languages.

- input:

- Get data from the the "outside world". This might be

reading data from a file, or even some kind of sensor like

a microphone or GPS. In our initial programs, our input will come from the user

typing data on the keyboard.

- output:

- Display the results of the program on a screen

or store them in a file or perhaps write them to a device like a

speaker to play music or speak text.

- sequential execution:

- Perform statements one after

another in the order they are encountered in the script.

- conditional execution:

- Check for certain conditions and

execute or skip a sequence of statements.

- repeated execution:

- Perform some set of statements

repeatedly, usually with

some variation.

- reuse:

- Write a set of instructions once and give them a name

and then reuse those instructions as needed throughout your program.

It sounds almost too simple to be true and of course it is never

so simple. It is like saying that walking is simply

"putting one foot in front of the other". The "art"

of writing a program is composing and weaving these

basic elements together many times over to produce something

that is useful to its users.

The word counting program above directly uses all of

these patterns except for one.

1.10 What could possibly go wrong?

As we saw in our earliest conversations with Python, we must

communicate very precisely when we write Python code. The smallest

deviation or mistake will cause Python to give up looking at your

program.

Beginning programmers often take the fact that Python leaves no

room for errors as evidence that Python is mean, hateful and cruel.

While Python seems to like everyone else, Python knows them

personally and holds a grudge against them. Because of this grudge,

Python takes our perfectly written programs and rejects them as

"unfit" just to torment us.

>>> primt 'Hello world!'

File "<stdin>", line 1

primt 'Hello world!'

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> primt 'Hello world'

File "<stdin>", line 1

primt 'Hello world'

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> I hate you Python!

File "<stdin>", line 1

I hate you Python!

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> if you come out of there, I would teach you a lesson

File "<stdin>", line 1

if you come out of there, I would teach you a lesson

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>>

There is little to be gained by arguing with Python. It is a tool,

it has no emotion and it is happy and ready to serve you whenever you

need it. Its error messages sound harsh, but they are just Python's

call for help. It has looked at what you typed, and it simply cannot

understand what you have entered.

Python is much more like a dog, loving you unconditionally, having a few

key words that it understands, looking you with a sweet look on its

face (>>>) and waiting for you to say something it understands.

When Python says "SyntaxError: invalid syntax", it is simply wagging

its tail and saying, "You seemed to say something but I just don't

understand what you meant, but please keep talking to me (>>>)."

As your programs become increasingly sophisticated, you will encounter three

general types of errors:

- Syntax errors:

- These are the first errors you will make and the easiest

to fix. A syntax error means that you have violated the "grammar" rules of Python.

Python does its best to point right at the line and character where

it noticed it was confused. The only tricky bit of syntax errors is that sometimes

the mistake that needs fixing is actually earlier in the program than where Python

noticed it was confused. So the line and character that Python indicates in

a syntax error may just be a starting point for your investigation.

- Logic errors:

- A logic error is when your program has good syntax but there is a mistake

in the order of the statements or perhaps a mistake in how the statements relate to one another.

A good example of a logic error might be, "take a drink from your water bottle, put it

in your backpack, walk to the library, and then put the top back on the bottle."

- Semantic errors:

- A semantic error is when your description of the steps to take

is syntactically perfect and in the right order, but there is simply a mistake in

the program. The program is perfectly correct but it does not do what

you intended for it to do. A simple example would

be if you were giving a person directions to a restaurant and said, "... when you reach

the intersection with the gas station, turn left and go one mile and the restaurant

is a red building on your left.". Your friend is very late and calls you to tell you that

they are on a farm and walking around behind a barn, with no sign of a restaurant.

The you say "did you turn left or right gas station?" and

they say, "I followed your directions perfectly, I have

them written down, it says turn left and go one mile at the gas station.". Then you say,

"I am very sorry, because while my instructions were syntactically correct, they

sadly contained a small but undetected semantic error.".

Again in all three types of errors, Python is merely trying its hardest to

do exactly what you have asked.

1.11 The learning journey

As you progress through the rest of the book, don't be afraid if the concepts

don't seem to fit together well the first time. When you were learning to speak,

it was not a problem for your first few years you just made cute gurgling noises.

And it was OK if it took six months for you to move from simple vocabulary to

simple sentences and took 5-6 more years to move from sentences to paragraphs, and a

few more years to be able to write an interesting complete short story on your own.

We want you to learn Python much more rapidly, so we teach it all at the same time

over the next few chapters.

But it is like learning a new language that takes time to absorb and understand

before it feels natural.

That leads to some confusion as we visit and revisit

topics to try to get you to see the big picture while we are defining the tiny

fragments that make up the big picture. While the book is written linearly and

if you are taking a course, it will progress in a linear fashion, don't hesitate

to be very non-linear in how you approach the material. Look forwards and backwards

and read with a light touch. By skimming more advanced material without

fully understanding the details, you can get a better understanding of the "why?"

of programming. By reviewing previous material and even re-doing earlier

exercises, you will realize that you actually learned a lot of material even

if the material you are currently staring at seems a bit impenetrable.

Usually when you are learning your first programming language, there are a few

wonderful "Ah-Hah!" moments where you can look up from pounding away at some rock

with a hammer and chisel and step away and see that you are indeed building

a beautiful sculpture.

If something seems particularly hard, there is usually no value in staying up all

night and staring at it. Take a break, take a nap, have a snack, explain what you

are having a problem with to someone (or perhaps your dog), and then come back it with

fresh eyes. I assure you that once you learn the programming concepts in the book

you will look back and see that it was all really easy and elegant and it simply

took you a bit of time to absorb it.

1.12 Glossary

- bug:

- An error in a program.

- central processing unit:

- The heart of any computer. It is what

runs the software that we write; also called "CPU" or "the processor".

- compile:

- To translate a program written in a high-level language

into a low-level language all at once, in preparation for later

execution.

- high-level language:

- A programming language like Python that

is designed to be easy for humans to read and write.

- interactive mode:

- A way of using the Python interpreter by

typing commands and expressions at the prompt.

- interpret:

- To execute a program in a high-level language

by translating it one line at a time.

- low-level language:

- A programming language that is designed

to be easy for a computer to execute; also called "machine code" or

"assembly language."

- machine code:

- The lowest level language for software which

is the language that is directly executed by the central processing unit

(CPU).

- main memory:

- Stores programs and data. Main memory loses

its information when the power is turned off.

- parse:

- To examine a program and analyze the syntactic structure.

- portability:

- A property of a program that can run on more

than one kind of computer.

- print statement:

- An instruction that causes the Python

interpreter to display a value on the screen.

- problem solving:

- The process of formulating a problem, finding

a solution, and expressing the solution.

- program:

- A set of instructions that specifies a computation.

- prompt:

- When a program displays a message and pauses for the

user to type some input to the program.

- secondary memory:

- Stores programs and data and retains its

information even when the power is turned off. Generally slower

than main memory. Examples of secondary memory include disk

drives and flash memory in USB sticks.

- semantics:

- The meaning of a program.

- semantic error:

- An error in a program that makes it do something

other than what the programmer intended.

- source code:

- A program in a high-level language.

1.13 Exercises

Exercise 1

What is the function of the secondary memory in a computer?

a) Execute all of the computation and logic of the program

b) Retrieve web pages over the Internet

c) Store information for the long term - even beyond a power cycle

d) Take input from the user

Exercise 2

What is a program?

Exercise 3

What is is the difference between a compiler and an interpreter?

Exercise 4

Which of the following contains "machine code"?

a) The Python interpreter

b) The keyboard

c) Python source file

d) A word processing document

Exercise 5

What is wrong with the following code:

>>> primt 'Hello world!'

File "<stdin>", line 1

primt 'Hello world!'

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>>

Exercise 6

Where in the computer is a variable such as "X" stored

after the following Python line finishes?

x = 123

a) Central processing unit

b) Main Memory

c) Secondary Memory

d) Input Devices

e) Output Devices

Exercise 7

What will the following program print out:

x = 43

x = x + 1

print x

a) 43

b) 44

c) x + 1

d) Error because x = x + 1 is not possible mathematically

Exercise 8

Explain each of the following using an example of a human capability:

(1) Central processing unit, (2) Main Memory, (3) Secondary Memory,

(4) Input Device, and

(5) Output Device.

For example, "What is the human equivalent to a Central Processing Unit"?

Exercise 9

How do you fix a "Syntax Error"?

- 1

- http://xkcd.com/231/